In terms of art, appropriation is the intentional borrowing, copying, and alteration of preexisting images and objects. It is a strategy that has been used by artists for millennia. Surrealist artists Georges Braque, Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst among others used the process frequently. It continues to be significant as the world becomes more consumer oriented, and as we experience a proliferation of popular images through mass media outlets from magazines to television to the Internet.

In the 1980’s artist Sherry Levine often used appropriation and revision. Levine often reproduced as her own; work originally created by others with more than a nod to artists of the past, like Monet. She sought to create a new situation and new meaning in her own work while using images we might (or might not) recognize as first painted by others. Appropriation can be confusing, because the line between borrowing, appropriating, and copying it often quite blurry.

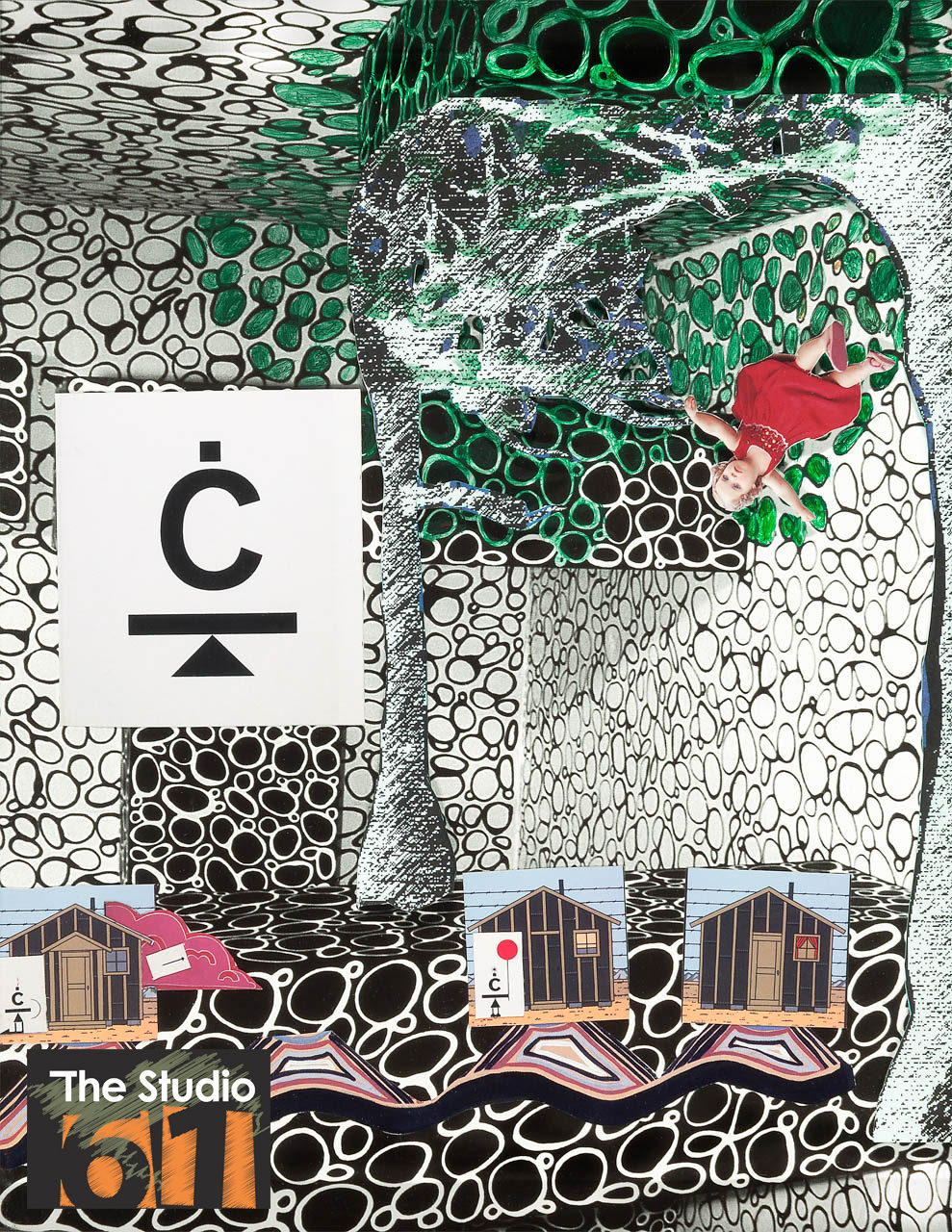

I find it challenging to create an artwork borrowing a composition, a portion of another artist’s work or a photo from the newspaper revised for my own particular purpose. Sometimes I do one image that might include portions borrowed from four or five artists, or I might just select a composition I like and revise it. My purpose is not the same as the original artist and it has little to do with the borrowed image. Occasionally, a clever artist or art scholar will recognize what I have done, but that is seldom the case.

It can be a bit tricky, this appropriation and revision. I enjoy walking the line, testing boundaries with my work, which makes it more intellectual than expressive. Sometimes I am just so in love with what I have learned by studying the work of someone that I admire, the result is more of homage to my unknown mentor.

Appropriation art raises questions of originality, authenticity and authorship, and because of this it is a useful tool for exploring these concepts. As such, it belongs to a long tradition that goes beyond using art as a tool for showing images and narratives and looks inward instead, questioning the nature of art itself.